Pediatric Liver Transplant

The UCSF Liver Transplant Program is one of the nation's leading liver transplant centers for both children and adults and has been designated a "Center of Excellence" by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Children who receive livers at UCSF have a survival rate of more than 95 percent after one year and 90 percent after five years, well above the national average. Our program also has one of the lowest re-transplantation rates in the country. After liver transplant, most children return to a normal quality of life and catch up or accelerate in growth. We have a number of former patients who have given birth to their own healthy children.

Our primary goal is to return patients to a "normal" lifestyle as soon as possible. To accomplish this, we have a comprehensive approach to patient care. The program's internationally recognized surgical team is supported by specialists in gastroenterology, infectious disease, anesthesiology, liver disease and pharmacology as well as by nurse coordinators, social workers, mental health professionals, a nutritionist and financial counselors.

For many years, one of the challenges to doing liver transplants in children was the difficulty of finding small livers from deceased donors. However, a new procedure allows living donors to donate a segment of their liver, which grows to the appropriate size in the child. The donor's remaining liver will regenerate, eventually growing back to its original size. UCSF's team was among the first in the world to perform this surgery.

Our liver transplant research has included testing new anti-rejection drugs, contributing to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Liver Transplant Database and establishing procedures for treating Hepatitis B and liver cancer patients with transplants.

Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation, first performed in 1963, provides an opportunity for a longer, more active life for people in the final stages of liver disease. Advances in surgical techniques and new medications that prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted organ have greatly improved success rates.

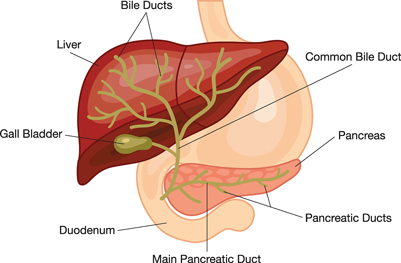

The largest organ in the body, the liver performs many complicated functions, including processing proteins, fats and carbohydrates and breaking down toxic substances such as drugs and alcohol. In addition, the liver makes the chemical components that help blood to clot. If the liver fails, the body loses the ability to clot blood as well as to process nutrients needed for life.

The liver also excretes a yellow digestive juice called bile, which may accumulate if the liver is not working properly. The eyes may become "jaundiced" or yellow, or the skin may itch from the accumulated bile. Some medications help treat the symptoms of liver failure, but there are no drugs that cure liver failure.

Evaluation

Most liver transplant patients at UCSF are referred to the program by primary care doctors or by a specialist. When a referral is made, a transplant program coordinator will call you to schedule an appointment, typically on a Tuesday.

Preliminary Evaluation

A preliminary evaluation is the first step in helping you and the transplant team determine whether transplantation is an appropriate treatment for your child. It also enables the transplant team to assess the medical factors related to your child's liver failure. Not everyone who is evaluated for a liver transplant actually needs one. Your initial appointment will help determine your child's treatment options.

The preliminary evaluation will take a full day, from about 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., and can be very tiring. The following tips will help you prepare for this first appointment:

- If possible, bring family members or close friends to help you understand and remember the significant amount of information you will be receiving about the transplantation process.

- Because your child will be undergoing many tests, don't let him or her eat or drink anything after midnight of the day before your appointment. Plan to bring a snack.

- Please bring any medications your child is taking, your health insurance information and your child's medical records if you have them.

As part of the evaluation, a series of tests will be conducted, including:

- Blood tests to help determine how well your child's liver is functioning and to assess kidney function.

- Chest X-ray to help detect infection in your child's lungs and assess the status of your child's bones.

- Electrocardiogram to help identify any changes in your child's heart rhythm.

- Pulmonary function test to measure your child's lung capacity. Your child will be asked to breathe into a machine, and blood will be drawn to determine how well oxygen is being absorbed from his or her lungs.

- Ultrasound to view the blood flow to and from your child's liver and to locate any abnormal masses in the liver.

A liver specialist, called a hepatologist, and a surgeon will also evaluate your child. The hepatologist will do a full exam, review your child's health history and discuss what it means to be on the transplant waiting list.

You can discuss your test results with the hepatologist and surgeon and both will answer any questions you have. Many parents find it helpful to write down their questions before the appointment.

You will also meet with a financial counselor to review your insurance information.

Waiting For a Transplant

Once the evaluation is complete, the transplant team meets to discuss each case and to decide whether to add your child to the national waiting list for available livers. Once on the waiting list, you will be notified and your child will undergo further testing at your local doctor's office.

Parents with children on the cadaveric waiting list will receive instructions about getting a pager and informing the team about changing health conditions. Since a donor liver may become available at any time of the day or night, you must carry a pager with you at all times and keep it turned on when you're not at home. The wait for a new liver is generally two to three years.

When a donor becomes available, careful testing is performed to ensure that the organs are not damaged in any way. Then, they are matched to a transplant candidate of compatible size and blood type. In some cases, the team may conclude that the donor liver is not satisfactory. If this occurs, the transplant will be canceled. If a cancellation occurs, remember that it is in your child's best interest.

Before your child's operation, a social worker will talk to you to about his or her adjustment after the surgery. Individual counseling is also available during your hospital stay. If necessary, a social worker can arrange follow-up services and answer questions about disability.

Living Donor Liver Transplantation

Transplant livers may come from a cadaveric donor who has died, or from a living donor. A living donor is usually someone in the family or a close family friend. Living donor liver transplantation allows surgeons to perform the transplant without the sometimes-lengthy wait for a cadaveric liver. Both donor and recipient livers grow and regenerate after the transplant. During the transplant evaluation, we will discuss living donor transplants with you.

Donor safety is of primary concern throughout the process. Donors must be in good health, have a blood type that's compatible with the recipient and be motivated to donate by altruistic reasons. If live donation is suitable for your child, a donor evaluation will be started after all of your child's testing is complete. If the transplant team determines the donation would work, a surgery date is scheduled for both your child and your child's donor. This whole process usually takes up to six months.

Procedure

Your child's surgery may take from four to 12 hours depending on his or her condition. During surgery, your child's old liver and gallbladder will be removed and replaced with the donor liver. Since a gallbladder is no longer needed, a new one will not be transplanted.

After surgery, your child will go directly to the intensive care unit (ICU), usually for one to two days. Immediately after surgery, a breathing tube will be inserted to help him or her breathe. In most cases the tube can be removed within 24 hours after surgery. Many monitoring lines will be attached; these, too, will be removed as your child becomes more stable. When your child is ready to leave the ICU, he or she will be cared for on either the sixth or seventh floor of the hospital.

Liver Transplant Recovery

Everyone recuperates from liver transplantation differently. Depending on your child's condition, he or she will be hospitalized for two to eight weeks following the transplant. Most children stay within the San Francisco Bay Area for two to six weeks after the transplant and then are referred back to their primary care doctor and referring physician. Our social workers will assist you with temporary housing.

Once your child has returned home, we work with your primary doctors to ensure that your child receives optimum care, both for the liver transplant as well as issues related to normal growth and development.

Laboratory blood tests are obtained twice a week following transplantation; the frequency of blood tests is gradually reduced over time. You will be asked to call in test results to the transplant office. You will then be notified about any adjustments in your child's medications.

Potential Complications

Complications can occur with any kind of surgery, and patients undergoing organ transplants may face additional complications. The life-threatening disease that created the need for your child's transplant may affect the functioning of other body systems. Other problems, such as rejection of the new liver, may also occur.

Some possible transplant complications and medication side effects include:

- Hemorrhage — One function of the liver is to make chemical components used to help blood clot, called clotting factors. When a liver fails, the ability to produce clotting factors is impaired. To correct this problem, your child will receive blood products before and after surgery. We expect that the new liver will start working very quickly to help prevent any excessive bleeding, but your child may need to return to surgery to control the bleeding, particularly if it occurs within the first 48 hours after transplant.

- Thrombosis — If a blood clot forms in a vessel leading to or from your child's liver, this may injure the new liver. Your child will receive special anticoagulation medication to prevent this. This is a serious complication that may require a second transplant.

- Rejection — Your child's immune system protects him or her from invading organisms. Unfortunately, it also views the new liver as foreign and will try to destroy it in an attempt to protect your child. This is known as rejection. To prevent this from occurring, your child must take special immunosuppressive medication for the rest of his or her life.

Rejection can be diagnosed early by performing weekly liver biopsies during the first few weeks after liver transplant. Although rejection is common, with early diagnosis and treatment the situation can be controlled in more than 95 percent of cases.

Immunosuppressive Medications

These drugs decrease your child's resistance to foreign bodies, such as the new liver. Your child will need to take these medications for the rest of his or her life or the liver will be rejected. Immediately after surgery, the dosages will be high since the probability of rejection is greatest at this time. Dosages will be lowered quickly to smaller amounts if there are no signs of rejection.

The medications have side effects, which are usually dose-related. Most people experience the most side effects in the beginning when medication dosages are high. As the dosage is lowered, these effects will probably lessen. Side effects may occur in some patients and not in others.

The medications your child will take for rejection also impair his or her ability to fight off infections. Your child will be given medication to help prevent infections but you also will need to use caution and avoid contact with people with infections, especially during the first three to six months after transplant.

Reviewed by health care specialists at UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital.