Kidney Transplant

Chronic kidney disease is a major health concern in this country afflicting more than eight million Americans. When kidney function declines to a certain level, patients have end-stage renal disease and require either dialysis or transplantation to sustain their life. Currently more than 340,000 people are on dialysis, with 106,000 new patients added in 2006. Over 140,000 people are living with a functioning kidney transplant (source: www.usrdsrg). The prevalence of these two populations of end-stage renal disease has tripled in the last 20 years. Medicare expenditure for end-stage renal disease is expected to exceed $28 billion in 2010.

In 2006, 10,659 patients received a deceased donor kidney transplant and 6,432 patients received a live donor kidney transplant. However, more than 74,000 people are currently on the national waiting list for a deceased donor kidney transplant (source: www.usrds.org). Despite the increasing numbers of kidney transplants performed each year, the waiting list continues to grow. Twelve people die each day awaiting a kidney transplant.

Normal Kidney Function

The kidneys are organs whose function is essential to maintain life. Most people are born with two kidneys, located on either side of the spine, behind the abdominal organs and below the rib cage. The kidneys perform several major functions to keep the body healthy.

- Filtration of the blood to remove waste products from normal body functions, passing the waste from the body as urine, and returning water and chemicals back to the body as necessary.

- Regulation of the blood pressure by releasing several hormones.

- Stimulation of production of red blood cells by releasing the hormone erythropoietin.

The normal anatomy of the kidneys involves two kidney bean shaped organs that produce urine. Urine is then carried to the bladder by way of the ureters. The bladder serves as a storehouse for the urine. When the body senses that the bladder is full, the urine is excreted from the bladder through the urethra.

Kidney Disease

When the kidneys stop working, renal failure occurs. If this renal failure continues (chronically), end-stage renal disease results, with accumulation of toxic waste products in the body. In this case, either dialysis or transplantation is required.

Common Causes of End-Stage Renal Disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- High blood pressure

- Glomerulonephritis

- Polycystic Kidney Disease

- Severe anatomical problems of the urinary tract

Treatments for End-stage Renal Disease

The treatments for end-stage renal disease are hemodialysis, a mechanical process of cleaning the blood of waste products; peritoneal dialysis, in which waste products are removed by passing chemical solutions through the abdominal cavity; and kidney transplantation.

However, while none of these treatments cure end-stage renal disease, a transplant offers the closest thing to a normal life because the transplanted kidney can replace the failed kidneys. However, it also involves a life-long dependence on drugs to keep the new kidney healthy. Some of these drugs can have severe side effects.

Some kidney patients consider a transplant after beginning dialysis; others consider it before starting dialysis. In some circumstances, dialysis patients who also have severe medical problems such as cancer or active infections may not be suitable candidates for a kidney transplant.

Kidney Transplantation

Kidneys for transplantation come from two different sources: a living donor or a deceased donor.

The Living Donor

Sometimes family members, including brothers, sisters, parents, children (18 years or older), uncles, aunts, cousins, or a spouse or close friend may wish to donate a kidney. That person is called a "living donor." The donor must be in excellent health, well informed about transplantation, and able to give informed consent. Any healthy person can donate a kidney safely.

Deceased Donor

A deceased donor kidney comes from a person who has suffered brain death. The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act allows everyone to consent to organ donation for transplantation at the time of death and allows families to provide such permission as well. After permission for donation is granted, the kidneys are removed and stored until a recipient has been selected.

Transplant Evaluation Process

Regardless of the type of kidney transplant-living donor or deceased donor-special blood tests are needed to find out what type of blood and tissue is present. These test results help to match a donor kidney to the recipient.

Blood Type Testing

The first test establishes the blood type. There are four blood types: A, B, AB, and O. Everyone fits into one of these inherited groups. The recipient and donor should have either the same blood type or compatible ones, unless they are participating in a special program that allow donation across blood types. The list below shows compatible types:

- If the recipient blood type is A Donor blood type must be A or O

- If the recipient blood type is B Donor blood type must be B or O

- If the recipient blood type is O Donor blood type must be O

- If the recipient blood type is AB Donor blood type can be A, B, AB, or O

The AB blood type is the easiest to match because that individual accepts all other blood types.

Blood type O is the hardest to match. Although people with blood type O can donate to all types, they can only receive kidneys from blood type O donors. For example, if a patient with blood type O received a kidney from a donor with blood type A, the body would recognize the donor kidney as foreign and destroy it.

Tissue Typing

The second test, which is a blood test for human leukocyte antigens (HLA), is called tissue typing. Antigens are markers found on many cells of the body that distinguish each individual as unique. These markers are inherited from the parents. Both recipients and any potential donors have tissue typing performed during the evaluation process.

To receive a kidney where recipient's markers and the donor's markers all are the same is a "perfect match" kidney. Perfect match transplants have the best chance of working for many years. Most perfect match kidney transplants come from siblings.

Although tissue typing is done despite partial or absent HLA match with some degree of "mismatch" between the recipient and donor.

Crossmatch

Throughout life, the body makes substances called antibodies that act to destroy foreign materials. Individuals may make antibodies each time there is an infection, with pregnancy, have a blood transfusion, or undergo a kidney transplant. If there are antibodies to the donor kidney, the body may destroy the kidney. For this reason, when a donor kidney is available, a test called a crossmatch is done to ensure the recipient does not have pre-formed antibodies to the donor .

The crossmatch is done by mixing the recipient's blood with cells from the donor. If the crossmatch is positive, it means that there are antibodies against the donor. The recipient should not receive this particular kidney unless a special treatment is done before transplantation to reduce the antibody levels. If the crossmatch is negative, it means the recipient does not have antibodies to the donor and that they are eligible to receive this kidney.

Crossmatches are performed several times during preparation for a living donor transplant, and a final crossmatch is performed within 48 hours before this type of transplant.

Serology

Testing is also done for viruses, such as HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), hepatitis, and CMV (cytomegalovirus) to select the proper preventive medications after transplant. These viruses are checked in any potential donor to help prevent spreading disease to the recipient.

Phases of Transplant

Pre-transplant Period

This period refers to the time that a patient is on the deceased donor waiting list or prior to the completion of the evaluation of a potential living donor. The recipient undergoes testing to ensure the safety of the operation and the ability to tolerate the anti-rejection medication necessary after transplantation. The type of tests varies by age, gender, cause of renal disease, and other concomitant medical conditions. These may include, but are not limited to:

- General Health Maintenance: general metabolic laboratory tests, coagulation studies, complete blood count, colonoscopy, pap smear and mammogram (women) and prostate (men)

- Cardiovascular Evaluation: electrocardiogram, stress test, echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization

- Pulmonary Evaluation: chest x-ray, spirometry

Potential Reasons of Excluding Transplant Recipient

- Uncorrectable cardiovascular disease

- History of metastatic cancer or ongoing chemotherapy

- Active systemic infections

- Uncontrollable psychiatric illness

- Current substance abuse

- Current neurological impairment with significant cognitive impairment and no surrogate decision maker

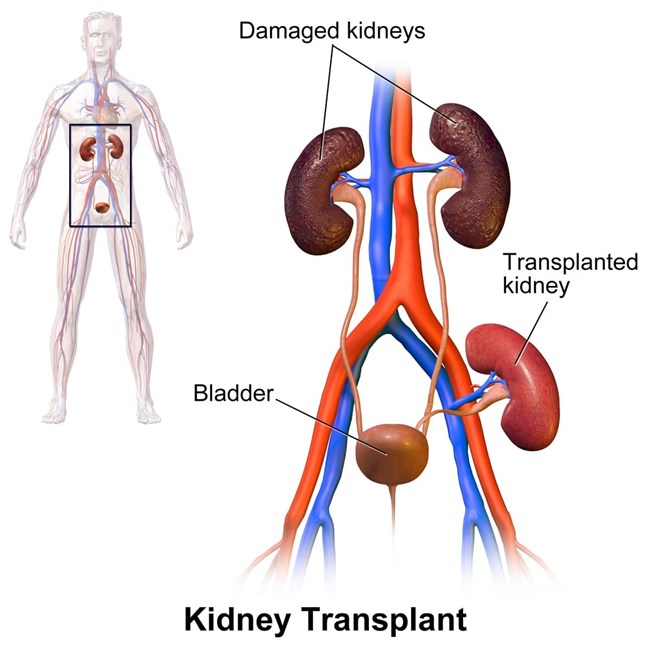

Transplant Surgery

The transplant surgery is performed under general anesthesia. The operation usually takes 2-4 hours. This type of operation is a heterotopic transplant meaning the kidney is placed in a different location than the existing kidneys. (Liver and heart transplants are orthotopic transplants, in which the diseased organ is removed and the transplanted organ is placed in the same location.) The kidney transplant is placed in the front (anterior) part of the lower abdomen, in the pelvis.

The original kidneys are not usually removed unless they are causing severe problems such as uncontrollable high blood pressure, frequent kidney infections, or are greatly enlarged. The artery that carries blood to the kidney and the vein that carries blood away is surgically connected to the artery and vein already existing in the pelvis of the recipient. The ureter, or tube, that carries urine from the kidney is connected to the bladder. Recovery in the hospital is usually 3-7 days.

Complications can occur with any surgery. The following complications do not occur often but can include:

- Bleeding, infection, or wound healing problems.

- Difficulty with blood circulation to the kidney or problem with flow of urine from the kidney.

These complications may require another operation to correct them.

By BruceBlaus - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=44925836

Post Transplant Period

The post transplant period requires close monitoring of the kidney function, early signs of rejection, adjustments of the various medications, and vigilance for the increased incidence of immunosuppression-related effects such as infections and cancer.

Just as the body fights off bacteria and viruses (germs) that cause illness, it also can fight off the transplanted organ because it is a "foreign object." When the body fights off the transplanted kidney, rejection occurs.

Rejection is an expected side effect of transplantation and up to 30% of people who receive a kidney transplant will experience some degree of rejection. Most rejections occur within six months after transplantation, but can occur at any time, even years later. Prompt treatment can reverse the rejection in most cases.

Anti-Rejection Medications

Anti-rejection medications, also known as immunosuppressive agents, help to prevent and treat rejection. They are necessary for the "lifetime" of the transplant. If these medications are stopped, rejection may occur and the kidney transplant will fail.

Below is a list of medications that might be used after a kidney transplant. A combination of these drugs will be prescribed dependent on the specific transplant needs.

Anti-inflammatory Medication

Prednisone is taken orally or intravenously. Most side effects of prednisone are related to drug dosage levels. Prednisone is used at low dosages to minimize side effects. The possible side effects of prednisone are:

- Changes in physical appearance such as puffiness of the face and weight gain.

- Irritation to the stomach lining.

- Increased risk of bruising and decreased rate of healing.

- Increased sugar level in the blood (steroid-induced diabetes).

- Unexplained mood changes. This may mean depression, irritability, or high spirits.

- General muscle weakness or pain in knees or joints.

- Formation of cataracts. A clouding of the lens of the eye occurs infrequently with long-term use of prednisone.

Anti-proliferative Medications

Azathioprine (Imuran®) is taken orally or intravenously. The most common side effects associated with azathioprine are:

- Thinning of hair

- Irritation of the liver

- Decreased white blood cell count

Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept®) is taken orally. The most common side effects of mycophenolate mofetil are:

- Abdominal aches and/or diarrhea

- Decreased white blood cell count

- Decreased red blood cell count

Mycophenolate sodium (Myfortic®) is taken orally. It provides the same active ingredient as mycophenolate mofetil and generally has the same side effect profile. It is enterically coated to potentially reduce abdominal aches and diarrhea.

Sirolimus (Rapamune®) is taken orally. The most common side effects of sirolimus are:

- Decreased platelet count

- Decreased white blood cell count

- Decreased red blood cell count

- Elevated cholesterol and triglycerides

Cytokine Inhibitors

Cyclosporine (Neoral®, Gengraf®) is taken orally. The most common side effects of cyclosporine therapy are:

- Kidney dysfunction

- Tremors

- Irritation of the liver

- Excessive body hair growth

- High blood pressure

- Swollen/bleeding gums

- High potassium in the blood

- Increased sugar level in the blood (drug-induced diabetes)

Tacrolimus (Prograf®) is taken orally. The most common side effects of tacrolimus therapy are:

- Kidney dysfunction

- High blood pressure

- High potassium in the blood

- Increased sugar level in the blood (drug-induced diabetes)

- Tremors

- Headaches

- Insomnia

Antilymphocyte Medications

Antithymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin®) is given intravenously. Thymoglobulin can cause:

- Decreased white blood cell and platelet counts

- Sweating

- Itching

- Rash

- Fever

Muromonab-CD3 (OKT3®) is given intravenously and can cause:

- Chills

- Fever

- Diarrhea

- Headache

- Shortness of breath

Anti-interleukin-2 Receptor Antibody (Zenapax® or Simulect®) These two drugs are given intravenously. These medications rarely cause side effects but can include:

- Chills

- Headache

- Allergic reaction

Alemtuzumab (Campath®)

- Fever

- Chills

- Rash

- Shortness of breath

- Decreased white blood cell counts

Living Donor Kidney Transplantation

Living donor kidney transplants are the best option for many patients for several reasons.

- Better long-term results

- No need to wait on the transplant waiting list for a kidney from a deceased donor

- Surgery can be planned at a time convenient for both the donor and recipient

- Lower risks of complications or rejection, and better early function of the transplanted kidney

Any healthy person can donate a kidney. When a living person donates a kidney the remaining kidney will enlarge slightly as it takes over the work of two kidneys. Donors do not need medication or special diets once they recover from surgery. As with any major operation, there is a chance of complications, but kidney donors have the same life expectancy, general health, and kidney function as most other people. The kidney loss does not interfere with a woman's ability to have children.

Potential Barriers to Living Donation

- Age < 18 years unless an emancipated minor

- Uncontrollable hypertension

- History of pulmonary embolism or recurrent thrombosis

- Bleeding disorders

- Uncontrollable psychiatric illness

- Morbid obesity

- Uncontrollable cardiovascular disease

- Conronic lung disease with impairment of oxygenation or ventilation

- History of melanoma

- History of metastatic cancer

- Bilateral or recurrent nephrolithiasis (kidney stones)

- Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) stage 3 or less

- Proteinuria > 300 mg/d excluding postural proteinuria

- HIV infection

If a person successfully completes a full medical, surgical, and psychosocial evaluation they will undergo the removal of one kidney. Most transplant centers in the United States use a laparoscopic surgical technique for the kidney removal. This form of surgery, performed under general anesthesia, uses very small incisions, a thin scope with a camera to view inside of the body, and wand-like instruments to remove the kidney. Compared with the large incision operation used in the past, laparoscopic surgery has greatly improved the donor's recovery process in several ways:

- Decreased need for strong pain medications

- Shorter recovery time in the hospital

- Quicker return to normal activities

- Very low complication rate

The operation takes 2-3 hours. Recovery time in the hospital is typically 1-3 days. Donors often are able to return to work as soon as 2-3 weeks after the procedure.

Occasionally the kidney needs to be removed through an open incision in the flank region. Prior to the use of the laparoscopic technique, this surgery was the standard for the removal of the donated kidney. It involves a 5-7 inch incision on the side, division of muscle and removal of the tip of the twelfth rib. The operation typically lasts 3 hours and the recovery in the hospital averages 4-5 days with time out of work of 6-8 weeks.

Although laparoscopy is increasingly used over open surgery, from time to time, the surgeon may elect to do an open procedure when individual anatomic differences in the donor suggest that this will be a better surgical approach.

The quality and function of the kidneys recovered with either technique work equally well. Regardless of technique all donors will require lifelong monitoring of their overall health, blood pressure and kidney function.

Special Programs For Living Donor Transplantation

Many patients have relatives or non-relatives who wish to donate a kidney but are not able to because their blood type or tissue type does not match. In such cases, the donor and recipient are said to be "incompatible."

See also: National Kidney Registry

Live Donor to Deceased Donor Waiting List Exchange

This program is a way for a living donor to benefit a loved one, even if their blood or tissue types do not match. The donor gives a kidney to another patient who has a compatible blood type and is at the top of the kidney waiting list for a "deceased donor" kidney. In exchange, that donor's relative or friend would move to a higher position on the deceased donor waiting list, a position equal to that of the patient who received the donor's kidney.

For example, if the donor's kidney went to the fourth patient on the deceased donor waiting list, the recipient would move to the fourth spot on the list for his or her blood group and would receive kidney offers once at the top of the list.

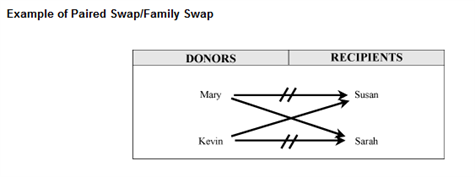

Paired Exchange Kidney Transplant (or "Family Swap")

This program is another way for a living donor to benefit a loved one even if their blood or tissue types do not match. A "paired exchange" allows patients who have willing but incompatible donors to "exchange" kidneys with one another-the kidneys just go to different recipients than usually expected.

An example of how this works would be if Mary wanted to give her sister Susan a kidney, but differences in blood type made it impossible, and Kevin wanted to give his sister Sarah a kidney, but differences in blood type made that impossible (see picture below). A paired exchange would be arranged so that Mary would donate to Sarah and Kevin would donate to Susan. The two pairs can thus "exchange" kidneys so that both donors give kidneys and both patients receive kidneys.

That means that two kidney transplants and two donor surgeries will take place on the same day at the same time.

Blood Type Incompatible Kidney Transplant

This is a program that lets patients receive a kidney from a living donor who has an incompatible blood type. To be able to receive such a kidney, patients must undergo several treatments before and after the transplant to remove the harmful antibodies that can lead to rejection of the transplanted kidney.

A special process called plasmapheresis, which is similar to dialysis, is used to remove these harmful antibodies from the patient's blood.

Patients require multiple treatments with plasmapheresis before transplant, and may require several more after transplant to keep their antibody levels down. Some patients may also need to have their spleens removed at the time of transplant surgery to lower the number of cells that produce antibodies. The spleen, a spongy organ about as big as a person's fist, produces blood cells. Located in the upper left part of the abdomen under the rib cage, the spleen can be removed laparoscopically.

Positive Crossmatch and Sensitized Patient Kidney Transplant

This program makes it possible to perform kidney transplants in patients who have developed antibodies against their kidney donors-a situation known as "positive crossmatch."

The process is similar to that for blood type-incompatible kidney transplants. Patients receive medications to decrease their antibody level or they may undergo plasmapheresis treatments to remove the harmful antibodies from their blood. If their antibody levels to their donors are successfully reduced, they can then go ahead with the transplants.

Blood type-incompatible kidney transplants and positive crossmatch/sensitized patient kidney transplants have been very successful in the United States and internationally. Success rates are close to those for transplants from compatible living donors and are better than success rates for deceased donor transplants.

Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation

When an individual does not have a living donor but is an acceptable transplant candidate, he/she will be placed on a waiting list. In 1984, Congress passed the National Organ Transplant Act. This act prohibited the sale of human organs and mandated a national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) to oversee organ recovery and placement and equitable organ distribution policies. The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) is an independent, non-profit organization. It was awarded the national OPTN contract in 1986. It is the only organization ever to operate the OPTN.

Organ Procurement Organizations (OPO) are non-profit agencies operating in designated service areas covering whole states or just parts of a state. OPOs are responsible for: approaching families about the option of donation, evaluating suitability of potential donors, coordinating the recovery and transportation of donated organs and educating the public about the need for organ donation.

Most deceased donor kidneys are transplanted to recipients in the same service area as the deceased donor. Although there are recommended guidelines for organ allocation, each OPO may request a "variance" to fit the special needs to the patients waiting for kidney transplantation in their service area.

Whenever a donor is identified within an OPO the HLA tissue typing results are entered into the UNOS national computer system. UNOS has the HLA tissue typing information of all patients awaiting kidney transplantation in the United States. If a waiting list patient has the identical HLA tissue type as the donor the kidney will be given to him/her regardless of the geography.

Unfortunately, many more patients are medically suitable for transplants than organs available. The waiting times are many years and growing longer. Many patients develop medical and surgical complications while waiting which may prevent them from receiving a deceased donor kidney transplant in the future.

Special Programs For Deceased Donor Transplantation

Expanded Criteria Donor Program

Although the most commonly transplanted deceased donor kidneys come from previously healthy donors between the ages of 18 and 60, kidneys from other deceased donors have been successfully transplanted. The goal of this program is to use organs from less traditional donors more effectively so that more patients can receive kidney transplants.

Kidney Transplants from Less Traditional Deceased Donor Category

- Age 60 or older

- Between the ages of 50-59 with at least two of the following conditions:

- History of high blood pressure

- A serum creatinine (kidney function test) level greater than 1.5 (normal is 0.8-1.4)

- Cause of death was from a stroke or a brain aneurysm

Patients who are most likely to benefit from a kidney through this program are dialysis patients who are older and have a greater risk of problems, including death, while waiting for a transplant. Accepting a kidney from an expanded criteria donor may shorten the waiting period for a transplant. Patients who are considered for this type of transplant also remain on the waiting list for standard kidney offers.

Hepatitis C Donor Program

About 8% of patients on the deceased donor waiting list have the Hepatitis C virus. By accepting a kidney from a deceased donor who also had Hepatitis C, these patients could shorten the waiting time for a deceased donor kidney.

The use of kidneys from donors who had Hepatitis C does not appear to have a harmful effect on the survival of the transplanted kidney or on the overall health of the patient, provided that he or she has been evaluated carefully before receiving the transplant.

HIV Program

A growing number of patients with end-stage renal disease are infected with the HIV virus. Through the use of effective antiviral therapy, these patients are surviving on dialysis with their HIV disease and are being considered more and more frequently for kidney transplantation.

Transplant Success Rates

The success rate of kidney transplantation varies depending on whether the donated organ is from a living donor or a deceased donor as well as the medical circumstances of the recipient. Kidneys from living donors generally last longer. Most kidney losses are due to rejection, but infections, circulation problems, cancer, and return of the original kidney disease can also cause kidney loss.

| Type of Donor | 1 Year | 3 Years | 5 Years | 10 Years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Living Donor |

Graft survival |

95% |

88% |

80% |

57% |

|

Patient survival |

98% |

95% |

90% |

64% |

|

|

Deceased Donor |

Graft survival |

90% |

79% |

67% |

41% |

|

Patient survival |

95% |

88% |

81% |

61% |

Source: SRTR -- Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

In contrast, dialysis patients have 4-7 fold greater chance of dying as compared to transplant recipients.

Current Issues in Kidney Transplantation

Kidney Allocation Policies

Currently the organ supply cannot meet the demand and there is no foreseeable end to the problem. Patients wait many years for a transplant. People are dying or becoming medically unsuitable for transplantation as these waiting times grow longer. Also, there are significant geographic differences in access to transplantation and wait times.

As each organ is a precious resource that should be utilized for maximum efficiency, the transplant community is changing the way kidneys are distributed to patients on the waiting list. Some patients may benefit, others are disadvantaged, and a delicate balance must be struck between fairness and equality.

On one hand, organs are a scarce resource and could be given to patients who would maximize the duration of the transplanted organ. In contrast organs are a societal resource that could be distributed to all potential patients based on waiting time. These two views represent utility versus equity in organ allocation. The final decision regarding the allocation policy will likely fall somewhere in between the two viewpoints.

Xenotransplantation (transplant across species)

Even with creative ways to utilize more living and deceased donors, another source of kidneys is most likely necessary. Xenotransplantation has already occurred from non-human primate donors such as chimpanzees, monkeys and baboons.

However these animals are endangered species and the size and blood type differences as well as the concern of transmission of infectious diseases has led to a ban of these transplants by the Food and Drug Administration. Currently most of the research in this field is centered on the pig as the potential xenograft donor. Pigs have desirable characteristics: multiple offspring, rapid maturity to adult age, lower risk of transmissible infectious diseases and appropriate size.

The many barriers to successful xenotransplantation are under study and continued advances may lead to this type of transplantation solving the organ shortage crisis.

Transplant Tourism

With the short supply of organs and long waiting times, patients are now traveling outside of the United States to receive a kidney transplant. Commercialism and poor regulation can undermine the true nature of transplantation and put patient's lives at risk.

Tolerance

Lifelong immunosuppression is a tremendous burden on patients. Tolerance, or the ability of the body to "accept" an organ without daily anti-rejection medication has been the "Holy Grail" of transplantation. Many animal models as well as isolated reports of patients being withdrawn from these medications are encouraging.

Most of the successful models incorporate intensive medication at the time of transplant with bone marrow infusions from the donor that supplied the organ. The recipient incorporates the bone marrow cells, becomes "chimeric" and the new bone marrow cells re-educate the recipient to accept the organ. There are many issues to be refined in human transplantation but scientists and clinicians are working together to eliminate the need for lifelong immunosuppression.

Kidney Transplantation Clinical Trials

Continued advances in our understanding of the mechanisms involved in the acceptance of a kidney transplant has led to new and exciting medications. After testing the new medications in animal models, these drugs move into human clinical trials. The great success of transplantation has occurred as a result of basic science research, careful testing of innovative medications and patients' willingness to participate in controlled studies of new medications. Even tolerance protocols will require short term administration of new immunosuppressive medication. The cooperation and participation of patients in clinical trials is essential to keep the field of kidney transplantation moving forward.